For RPS (The Royal Photographic Society Journal)

By Nadia Marks

The Photographer, His Wife, Her Lover.

An extraordinary documentary film by Paul Yule will be on our TV screens this October. It will follow the drama behind one of the great art scandals of modern times in a complicated triangle between the celebrated American photographer O Winston Link, his wife and her lover. Nadia Marks talks to the films director and writer Paul Yule.

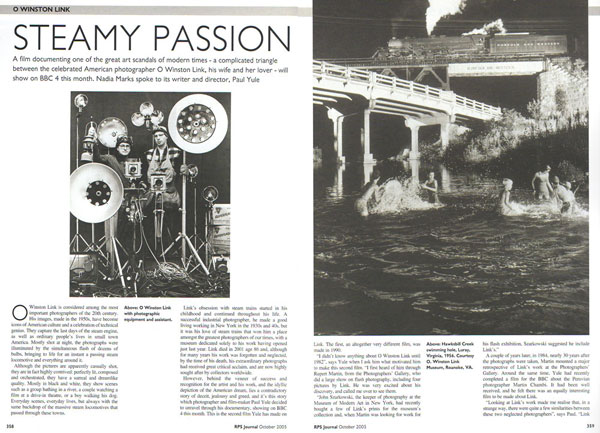

O. Winston Link’s work is considered amongst the most important photographic achievements of the 20th Century and he is undoubtedly one of the giants of contemporary photography. His images, made in the 1950s, have become icons of American culture and a celebration of technical genius. They capture the last days of the steam engine as well as ordinary people’s lives at a time of innocence and romance in small town America. Mostly shot at night, the photographs were illuminated by the simultaneous flash of dozens of bulbs bringing to life for an instant a passing steam locomotive and everything around it.

Although the pictures show scenes from ordinary life, apparently casually shot, they are in fact totally contrived; perfectly lit, perfectly composed and orchestrated they have a surreal and dream like quality. Mostly in black and white, they show scenes like groups of people bathing in a river, a couple watching a film in a drive-in theatre, or a boy walking his dog. Everyday scenes, everyday lives, but always with the same back drop of the massive steam locomotives that passed through these towns.

Link’s obsession with the steam trains started in his childhood and continued throughout his life. A very successful freelance industrial photographer he made a good living working in New York in the 1930s and 40s, but it was his love of steam trains that won him a place amongst the greatest photographers of our times, with a museum dedicated solely to his work having opened just last year. Winston Link died in 2001 age 86 and, although for many years his work was forgotten and neglected, by the time of his death his extraordinary photographs had received great critical acclaim and are now highly sought after by collectors around the world.

However, behind the veneer of success and recognition for the artist and his work, and the idyllic depiction of the American dream, lies a contradictory story of deceit, jealousy and greed, and it’s a story which photographer and film-maker Paul Yule decided to unravel through a documentary film to be shown in October on BBC 4. This is the second documentary Paul Yule has made on O. Winston Link. The first, an altogether a very different sort of film, was made in 1990.

“I didn’t know anything about O. Winston Link until 1982,” Yule explains when I ask him what motivated him to make this second film. “I first heard of him through Rupert Martin, from the Photographers Gallery who did a large show on flash photography, which included four pictures by O. Wiston Link. He was very excited about his discovery and called me over to show them to me.” Link at that time was pretty much forgotten and not really doing much with his work.

“Rupert Martin was told about Link’s work by John Szarkowski, the keeper of photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Szarkowski had recently bought a few of Link’s prints for the museum’s collection and when Martin was looking for work for his flash exhibition Szarkowski suggested he included Link’s photography.”

A couple of years later, in 1984, nearly 30 years after the photographs were taken Martin decided to mount a major retrospective of Link’s work at the Photographers Gallery. Around the time of this exhibition Yule had recently completed a documentary film for the BBC about the Peruvian photographer Martin Chambi called Martin Chambi and the Heirs of the Incas.” The film was well received and he felt there was an equally interesting film to be made about O. Winston Link.

“Looking at Link’s work made me realise that in a strange way there were quite a few similarities between these two photographers,” says Paul. Both had been neglected and forgotten, Link had documented American life in the mid 20th Century while Chambi, who had been photographing people in Peru from the 1900s to the 1930s, was also making a record of his native country. “Both photographers happened to have exhibitions at The Photographers Gallery around the same time too” Paul continues, “and both had suddenly come into prominence in the 80’s. So in 1990 I decided to make a film about Link which I called Trains that Passed in the Night.”

Paul’s film was to play a very significant part in cementing and confirming Link’s reputation as a great iconic photographer of the 20th Century. “Link documented an important aspect of American history and his work in my opinion is unique. The preparation that went into making these pictures the technical expertise and complexity was immense. The most complex of his pictures would take up to a week to set up. He used old- style flash bulbs, Sylvania flash, the size of a 60 watt bulb. When these things went off it would be like 80,000 100 watt bulbs going off at the same time. It was an incredible engineering feat to get them all to go off at the same time. It generated a huge amount of light and to synchronise the shutter to open at the same time was incredible. He devised his own flash system in order to make this happen. Before he lit his pictures everything was black, so everything in them is entirely intentional and therefore I think he is the most painterly of all photographers. Between about 1955 and 1960 he photographed and recorded the last Class A, steam line, the North and Western, which, once replaced with the diesel trains, were to be lost for ever as were the towns they passed through.” Finally, the photographs that had been put away by Link and had gone unnoticed for 30 years were rediscovered and were now being seen and appreciated.

“At the time I made my first film on Link he was married and living with Conchita, who was also his agent, was about 20 years younger than him and a very dynamic, and vibrant person. She was a major presence on the scene and I dealt mainly with her when it came to making the film.” Conchita was a great admirer of Links pictures which she worked hard at promoting and bringing to the notice of the art world. “The two were running a very successful business, marketing and selling the photographs and sound recordings of steam trains that he had made in the 1950s, and Link’s reputation in the art world was growing, as were his prices. Prior to that his photos were only used as covers for the albums he made of rail road recordings which were mainly bought by railroad enthusiast.”

About three years after Paul’s first film was made there was news of a very acrimonious divorce between Link and Conchita and Paul kept getting messages and news cuttings from mutual acquaintances about the break up of the marriage. “Conchita apparently was accused of having imprisoned Winston in their house, which seemed very strange. I even got approached by ABC, the news network, wanting footage of Winston and Conchita together from my film, as I was the only one to have it. I refused because I thought it was a private matter and didn’t want to interfere.” After everything Conchita and Link did together and all her efforts to promote his work, the divorce settlement in 1993 was pitiful and all she was given was her car and a few belongings. When he was in the States, Paul visited Link a few times but no mention was ever made of what was about to happen. In 1996, Paul heard that Conchita had been charged with stealing part of Link’s archive material. “Some 1,500 photographs worth about $1.6 million were supposed to have been stolen by Conchita” Paul explains, “and she was sent to prison for six and half, to twenty years! I couldn’t quite believe what I was hearing. It all seemed so improbable.”

Conchita served her six and half years and was then released, by which time Winston Link had died. When she came out of prison, Conchita married her lover Ed Hayes, a steam engine engineer, but got arrested again, in a sting like operation, while she was trying to sell some prints and was sent back to prison. “It all seemed absolutely incredible and unbelievable,” Paul says of her second arrest. Amazed at what was going on, Paul decided to go back to America to find out what had taken place between Winston Link and Conchita.

“It turned out that while we were filming Trains that Passed in the Night when I took Winston for ten days to Virginia, where he had taken his original photographs, Conchita, who was left behind in upstate New York, began an affair with Ed Hayes, who was helping Winston restore his old steam engine. And that love affair was to be the root of all the future drama.” A drama that shook the art world, and destroyed the lives of everyone involved.

Paul determined to find out what actually went on – Winston Link of course had already died – decided to visit Conchita and Ed Hayes in prison and to make another film, not only picking up from where he left last time, but to find out Conchitas side of the story. “I started visiting Conchita in jail and amazed by the story that emerged during our filming. I called the film The Photographer, His Wife, Her Lover and as always a triangle is far from straight forward or simple.”

Paul Yule’s film The Photographer, His Wife, Her Lover will be screened on BBC 4