Deep in the Cypriot Troodos mountains on the western side of the island, lies a small village called Droushia. The name, according to some of the locals may derive from the Greek Cypriot word droshia meaning fresh and airy, presumably referring to the village’s alpine location which during the hot summer months is much needed.

Deep in the Cypriot Troodos mountains on the western side of the island, lies a small village called Droushia. The name, according to some of the locals may derive from the Greek Cypriot word droshia meaning fresh and airy, presumably referring to the village’s alpine location which during the hot summer months is much needed.

It was on a scorching day in early September while driving through the dusty Cypriot mountain roads that Simon Brown and I found ourselves in Droushia. I had heard much about this village from my father as it was my grandfather’s birthplace. But in those days the village was an isolated rural place that could only be reached by horse or donkey. The journey from Larnaka along the coast, was uncomfortably hot but as we snaked up the hills towards Droushia we could feel a welcome change in the air. For several days now, we had been researching a photographic project; roaming the island in a four-wheel-drive we were looking for suitable houses and their owners to photograph.

The idea had grown from an interesting discovery Simon and I had made on previous working trip to the island. We had repeatedly come across elderly individuals – men and women in their 80’s and 90’s, who were living happily in much the same way as they had done for the last fifty, sixty or even seventy years. Many were still living in the family homes they had grown up in, and, apart from some basic modern appliances like electric lights, gas cooker, fridge and the ubiquitous TV set and radio their homes appeared to have changed very little for the best part of a century.

Globalisation has eroded traditional values and ways of life almost everywhere, and Cyprus is no exception; the island’s cities pride themselves on their modernity and most houses these days are architecturally designed. But our previous visit had taken us into more remote parts of the country where we met many old folk who had invited us into their homes; happy to show us around dwellings which, although often quite primitive at first sight, were charming, joyful and very colourful. It gradually dawned on us both that we were privileged to see a timeless and unique way of life which would gradually disappear, along with this elderly population. It seemed very important to capture some essence of this special lifestyle – and the obvious way was to make a photographic record, while there was till time.

Globalisation has eroded traditional values and ways of life almost everywhere, and Cyprus is no exception; the island’s cities pride themselves on their modernity and most houses these days are architecturally designed. But our previous visit had taken us into more remote parts of the country where we met many old folk who had invited us into their homes; happy to show us around dwellings which, although often quite primitive at first sight, were charming, joyful and very colourful. It gradually dawned on us both that we were privileged to see a timeless and unique way of life which would gradually disappear, along with this elderly population. It seemed very important to capture some essence of this special lifestyle – and the obvious way was to make a photographic record, while there was till time.

Keen to pursue the idea, I approached the Cyprus Tourist Board for help. They welcomed our suggestion and with their generous offer of a small sponsorship – two air plane tickets, a hired car and accommodation – Simon and I set off on our quest.

Although Droushia was on our list to visit, it was thanks to a wrong turn that we eventually stumbled upon it. The village kafenion – coffee shop – in the main square was our first stop, and the proprietor, a cheerful man proudly sporting a lavish grey moustache rushed to welcome us with sweet Cypriot coffee, ice cold water and directions to the residential part of the village.

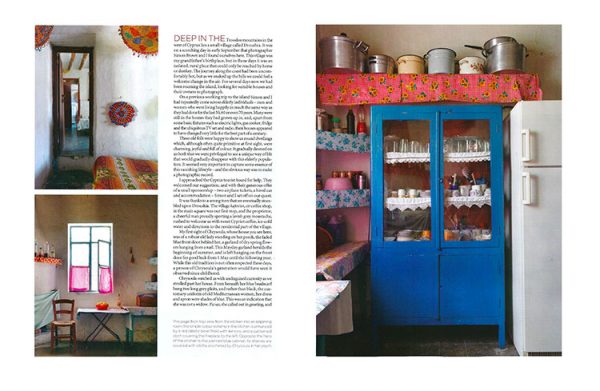

My first sight of Chrysoula was of a robust old lady standing on her front porch. The faded blue front door was behind her, a garland of dry spring flowers hanging from a nail. This May-day garland is a Greek tradition which heralds the beginning of summer and is left hanging on the front door for good luck from the 1st of May until the following year. While this old tradition is not often observed these days a person of Chrysoula’s generation would have seen it practised since childhood.

Chrysoula watched us with undisguised curiosity as we strolled past her house. From beneath her blue head scarf hung two long grey plaits, and rather than black – the customary uniform of old Mediterranean ladies her dress and apron were shades of blue. This was an indication that she was not a widow. Totally charmed I stopped and smiled her way, while Simon walked on unaware.

Chrysoula watched us with undisguised curiosity as we strolled past her house. From beneath her blue head scarf hung two long grey plaits, and rather than black – the customary uniform of old Mediterranean ladies her dress and apron were shades of blue. This was an indication that she was not a widow. Totally charmed I stopped and smiled her way, while Simon walked on unaware.

“Yia sas,” she called out in greeting and I tugged on Simon’s sleeve as she waved at us. “Ask her if we can photograph her” he whispered delighted by the image she presented.

“Why take a picture of me? I’m just an old woman!” she chuckled at my request, yet she nevertheless smiled and obliged. Then – as was so often to happen – we were invited into her home. ‘kopiaste’ she called out, beckoning us in as she pushed the front door open wide. Hospitality is a matter of ethnic pride for the Cypriots and no decent local would let a visitor walk by without an offer of welcome to their home.

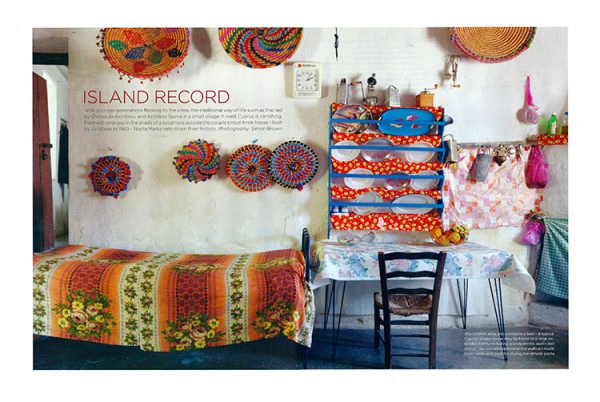

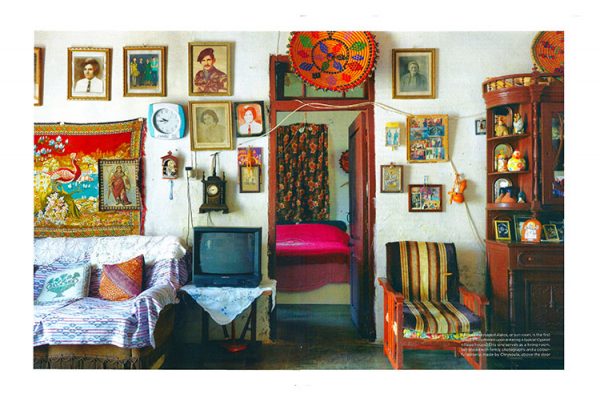

Once inside we both stood entranced by what we saw. For we had stepped into another time, another world. Just beyond the front door lay the first room, known in Greeks as the iliakos or ‘sun-room’; a large square entrance hall that leads to the rest of the house. This particular iliakos served as the living room, the TV set took centre stage, around which were scattered several sofas and chairs, myriad of photographs, wall hangings, and arty crafts. The total effect was a riot of colour. High up, close to the ceiling, like trophies, hung the paneria which Chrysoula proudly told us was her handywork. Woven from reeds, these flat baskets traditionally contained handmade pasta which was laid out to dry in the sun. Chrysoula confessed that she was never one to make pasta, but she explained that as a young woman she enjoyed making the paneria for purely decorative purposes – and for the colour they brought into the house. “They bring joy to the room,” she told us pointing at them.

The more we saw, the more we fell in love with her home. None of the rooms, apart from the main bedroom, seemed to have a sole purpose. What appeared to be the kitchen also contained a bed in, while another bedroom had an old fridge tucked alongside a bed or two. In the back yard stood an old traditional brick oven, and near by an outside toilet, while against the exterior wall of the house hang kitchen utensils, and against another wall, an old stone sink used for washing clothes and dishes. Visual anarchy reigned, but at the same time there was a synergy which made everything work.

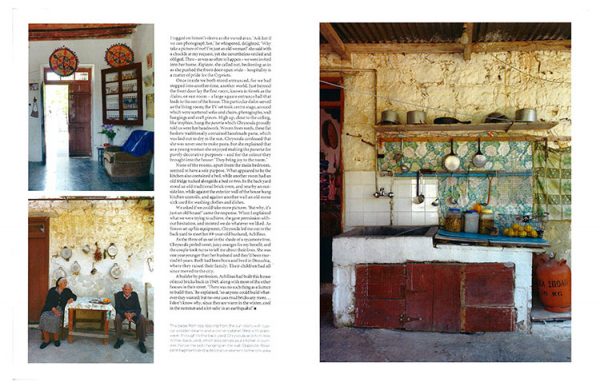

Totally inspired by what we saw we asked if we could take more pictures, and our request was met with the same perplex expression, as the old lady asked again, “But why, it’s just an old house!” When I explained what we were trying to achieve, she gave us permission without any hesitation and insisted we do what ever we liked. When Simon begun to set up his equipment, Chrysoula led me out to the back yard to meet her eight-nine year old husband Achilleas.

Totally inspired by what we saw we asked if we could take more pictures, and our request was met with the same perplex expression, as the old lady asked again, “But why, it’s just an old house!” When I explained what we were trying to achieve, she gave us permission without any hesitation and insisted we do what ever we liked. When Simon begun to set up his equipment, Chrysoula led me out to the back yard to meet her eight-nine year old husband Achilleas.

As we three sat in the shade of a sycamore tree Chrysoula peeled sweet juicy oranges for my benefit and they both took turns to tell me in Greek about their lives. She was one year younger than her husband she said and they’d been married 65 years. Both had been born and bred in Droushia, where they raised their family. Even though their children had all since moved to the city the couple would never dream of leaving their village and their home.

A builder by profession, Achilleas had built this house of mud bricks, back in 1949, along with most of the other houses in their street. “There was no such thing as a licence to build then,” he explained, “so anyone could build whatever they wanted, but no one uses mud bricks any more…” he lamented. “I don’t know why since they are warm in the winter, cool in the summer and a lot safer in an earthquake!”

©Nadia Marks 2014